The International Trade Blog Export Forms

U.S. - Chile Free Trade Agreement Rules of Origin

On: April 28, 2015 | By:  Sue Senger |

5 min. read

Sue Senger |

5 min. read

Exporters familiar with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the United States, Canada and Mexico (now USMCA) will recognize some aspects of the U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreement’s (FTA) Rules of Origin.

Exporters familiar with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the United States, Canada and Mexico (now USMCA) will recognize some aspects of the U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreement’s (FTA) Rules of Origin.

The Chile and U.S. FTA is largely modeled on the NAFTA. However, there are some important differences that require close attention.

Rules of origin are written in relation to the Harmonized System of Tariff Classification, also known as the Schedule B. The first step to using the Rules is to obtain the appropriate Schedule B code for the product in question.

A rule of origin may consist of:

1. A change in tariff classification;

2. A regional value-content requirement;

3. Both a change in tariff classification and a regional value content requirement.

It is necessary to refer to the rule associated with the product being exported. Regional Value Content can only be applied when it is allowed under a product-specific rule. The tariff schedule of the United States to implement the U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreement can be found at the United States International Trade Commission website.

To better understand how to apply these rules, here are some examples:

Simple Tariff Shift

Rule of Origin: "A change to heading 1902 through 1905 from any other chapter.”

Products: Breads, pastries, cakes, biscuits (HS 1905.90)

Non-U.S. or Chilean input: Flour (classified in HS chapter 11), imported from Europe.

Explanation: For all products classified in HS headings 1902 through 1905, all non-U.S. or Chilean inputs must be classified in an HS chapter other than HS chapter 19 in order for the product to obtain preferential duty treatment. These baked goods would qualify for tariff preference because the non-originating goods are classified outside of HS chapter 19. (The flour is in chapter 11). However, if these products were produced with non-originating mixes, then these products would not qualify because mixes are classified in HS chapter 19, the same chapter as baked goods.

Tariff Shift and Regional Value Content

Rule of Origin:

- “A change to subheading 9403.10 through 9403.80 from any other heading”; or

- “A change to subheading 9403.10 through 9403.80 from any other subheading, including another subheading within that group, provided there is a regional value content of not less than:

(a) 35 percent when the build-up method is used, or

(b) 45 percent when the build-down method is used.”

Product: Wooden Furniture (HS 9403.50)

Non-U.S. or Chilean input: Parts of furniture (classified in 9403.90), imported from Asia.

Explanation: Wooden furniture can qualify for preferential tariff treatment in two different ways—through a tariff shift, or a combination of a tariff shift and regional value content requirement.

Because the non-U.S. or Chilean input is classified in the same heading (9403) as the final product in this case, the good does not qualify under the simple tariff shift in the first rule. Moving down to the second rule, the good can meet the tariff shift because the non-originating component is from a different subheading than the final product. For the good to qualify as originating, however, it must also pass the regional value content test.

Regional Value Content

Regional Value Content

The Regional Value Content test allows the good to qualify using either one of two methods. These are the build-down and build-up methods.

Build-Down Method

Regional Value Content (RVC) = (((Adjusted value) - (Value of Non-Originating Materials)) / (Adjusted Value)) x 100

Build-Up Method

Regional Value Content (RVC) = ((Value of Originating Materials) / (Adjusted Value)) x 100

Using the example above, we will assume that the adjusted value for the piece of furniture in question is $1,000.

According to Article 4.3 of the U.S.-Chile FTA Rules of Origin, the value of non-originating materials used in the production of the good excludes:

- The cost of freight, insurance, packing and all other costs incurred in transporting the material to the location of the producer;

- Duties, taxes and customs brokerage fees on the material paid in the territory of one or both of the parties, other than duties and taxes that are waived, refunded, refundable or otherwise recoverable, including credit against duty or tax paid or payable;

- The cost of waste and spoilage resulting from the use of the material in the production of the good, less the value of renewable scrap or byproducts; and

- The cost of originating materials used in the production of the non-originating material in the territory of a party.

The assumed value of non-originating materials in this case is $500.

Plugging this into the build-down formula:

Regional Value Content (RVC) = (($1,000 – $500) / $1,000) x 100 = 50%

The percentage is greater than the 45% required by the rule; therefore, the good qualifies as originating.

Using the build-up formula:

Regional Value Content (RVC) = ($500 / $1,000) x 100 = 50%

The Regional Value Content is again 50% and is greater than the 35% required by the rule.

With either method, the good specified in this example qualifies as originating under the U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreement.

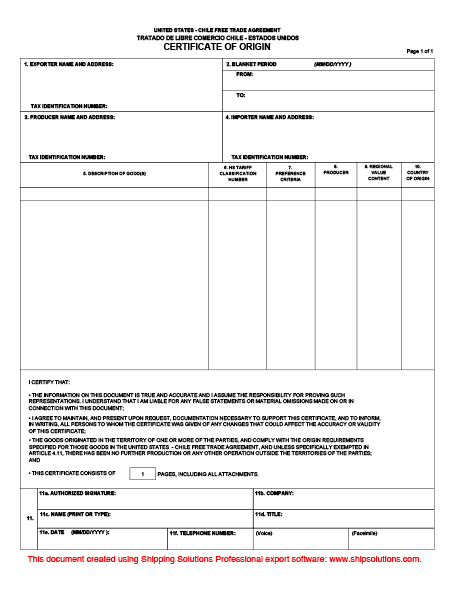

In order to take advantage of the benefits for U.S. goods under this agreement, exporters will need to understand how to determine that their goods are originating or qualify for preferential duty treatment under the U.S.-Chile FTA Rules of Origin. Once the determination is made, a U.S. - Chile Certificate of Origin form can be used to claim that preferential duty rate.

For more information about certificates of origin including other free trade agreement certificates, check out Using the Right Certificate of Origin for Your Exports.

This article, which was first published in March 2004, has been updated with additional information and current web links.

Like what you read? Subscribe today to the International Trade Blog to get the latest news and tips for exporters and importers delivered to your inbox.

About the Author: Sue Senger

Sue Senger is retired after a long career as an international trade consultant and faculty member at St. Paul College in St. Paul, Minnesota. She taught classes in Business Management, Supply Chain Logistics, Entrepreneurship/Marketing and Global Trade.